Perspectives from an English Historian who just happens to be Gay, Catholic, and a Democratic Socialist. Now back in the UK after 20 years of living in the United States. The Blog is eclectic in covering all these sides of my Life. Follow on Twitter at PaulBHalsall

Saturday, June 03, 2006

Anglo-Catholics and Decadence

1. the homosexual/aesthete connection in the Anglo-Catholic movement and

liturgy has *always* been fairly well know, although I suppose Geoffrey

Faber's Oxford Apostles: A Character Study of the Oxford Movement. 2nd ed..

[1936], really made it very clear. A more recent article is David Hilliard,

"Unenglish and Unmanly: Anglo-Catholicism and Homosexuality." Victorian

Studies 25:2 (Winter 1982), 181-210.

2. For a contemporary linking, see John Francis Bloxam: Story: The Priest

and the Acolyte, 1894 [From The Chameleon, December 1894

3. For the Roman Catholic side, see Ellis Hanson and Aubrey Beardsley,

Decadence and Catholicism (Harvard UP, 1998).

4. You can also read up on individual and group biography - for instance on

Aelred Carlyle and the Anglican monks of Caldey Island.

5. Some of what is quite well known, does not seem to have been printed -

for instance, the centrally important Anglo-Catholic church near High

Holborn that seems never to have had heterosexual clergy since its 19th

century foundation. Even today its annual feast-day mass is one of the

bigger unadvertised events in London.

6. The spirit of much anglo-catholicism, both its intrinsic aestheticism and

its sheer camp, did not really pass over into English (Roman) Catholicism,

which was much more plebian. Indeed, Cardinal Newman once made fun of those

who suggested that anyone with aesthetic feelings would convert to Roman

Catholicism for the beauty of liturgy. On the other hand, specific places

and groups within English Roman Catholicism did provide a respite from the

ferocious Irishness of English Catholic life. Specifically, the Oratorians

(especially at the high camp and aristocratic Brompton Oratory), the Order

of Preachers (Dominicans), and the Benedictines, were among the few places

Anglican converts could maintain what they liked in Anglo-Catholicism. [The

more butch joined the Jesuits, who never really seem to have understood

liturgy!]

Bindy Lambton

The Daily Telegraph

'Bindy' Lambton

(Filed: 19/02/2003)

"Bindy" Lambton, who died last Thursday aged 81, was the wife of Lord

Lambton, the former Conservative Minister, and a favourite subject, because

of her large-boned and angular beauty, for portraits by her friend Lucian

Freud.

Born Belinda Blew-Jones on December 23 1921, Bindy - as she was always

known - was the daughter of Major Douglas Holden Blew-Jones, of Westward Ho,

a tall, handsome officer in the Life Guards with size 24 feet. Her mother,

Violet Birkin, was one of three daughters of the Nottingham lace king, Sir

Charles Birkin.

Bindy dearly loved her father, but her relationship with her mother was

never close. Violet Blew-Jones drank too much, and proved a bad mother. She

abandoned the infant Bindy to the care of her beloved aunt, Mrs Freda Dudley

Ward, who was shortly to become engaged in a secret romance, conducted

throughout with the utmost discretion, with the then Prince of Wales (a

lesson which Bindy never forgot).

As well as being passionately fond of her Aunt Freda, Bindy idealised

Freda's daughters, Angie and Pempie Dudley Ward, and strove to be as

beautiful and popular as these two dazzling paragons; Angie married

Major-General Sir Robert Laycock, the Second World War commando leader,

while Pempie went on to become a famous actress and the wife of Sir Carol

Reed, the film director.

Bindy had no education, since she was expelled from 11 schools for various

wildnesses, only one of which is recorded - that of putting a bell-shaped

impediment under the headmistress's piano pedal.

Right from the start, however, Bindy's extraordinary individuality, handsome

good looks, high spirits and original wit began to attract an army of

life-long admirers. When she was 18 she met and married Tony Lambton, son of

the fifth Earl of Durham, and embarked enthusiastically on married life.

After producing her first daughter, Lucinda, she was told by many eminent

doctors on no account to have more children; but Bindy bravely produced four

more daughters, and the family moved to Biddick Hall, a perfect red brick

Queen Anne house on the Lambton estate in County Durham.

Having endured a rather sad, precarious childhood, Bindy Lambton was

determined that her own children should enjoy a perfect idyll. All her

fantasies of the ideal were brought into play, with lavish Christmases,

birthday parties, ponies and horse shows; later there were trips around

Britain and the Continent in a 50ft caravan, drawn by a Land Rover with

Bindy Lambton at the wheel, and often Lady Diana Cooper as second driver.

Blackpool illuminations were an annual treat, and to ensure privacy at

beauty spots she trained her army of children to fight and be naughty, to

see off the other tourists. Stately mansions, unused to caravans, were not

spared these visitations; but, because it was Bindy Lambton, all gates were

opened and all arms outstretched.

In the early 1950s Lord Lambton entered politics, as MP for

Berwick-upon-Tweed, with the backing and encouragement of Bindy. They

acquired a haunted Georgian house in Mayfair, 11 South Audley Street, which

Bindy Lambton furnished with notable good taste, and where the couple led a

glamorous life, providing her with the opportunity to give free bent to her

genius for lavish entertainment.

Never a martyr to the humdrum, Bindy Lambton created a fairyland of

joyousness which few could resist. The list of friends and admirers was

endless: Ari Onassis, Judy Montagu, Nancy Mitford (who described Bindy as

"blissful"), David Somerset, Jai and Ayesha Jaipur, Richard Sykes and also

such American illuminati as Jock and Betsy Whitney, Babe and Bill Paley,

Stash and Lee Radziwill, David O Selznick and his wife Irene, Jack and Drue

Heinz, Paul Getty and even Bing Crosby. All fell under her spell.

It was at this time, too, that she posed for the famous portraits by Lucian

Freud, with whom she watched the racing every afternoon on a flickering

black and white television set.

She also entertained generously at Biddick Hall, with a famous shoot and

wonderful food prepared by Berta, the cook, while lions and leopards which

the local butcher kept in the gardens roamed the bedrooms. Then, in 1961,

the longed-for son and heir Ned arrived.

Shortly thereafter the shadows began to fall.

First there was Bindy Lambton's go-karting accident, resulting in badly

shattered legs which had to be pinned together bone by bone by a

ground-breaking surgeon who was so frowned upon by the British medical

establishment that Bindy Lambton had to discharge herself from hospital to

be treated by him at the Dorchester Hotel. Then, just as her legs healed,

she drove into the path of a lorry on the A1.

This time virtually every bone in her body was broken, and she was not

expected to survive. But with characteristic fortitude she pulled through.

Encased in plaster like an Egyptian mummy - in which state she was

affectionately sketched by the great New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams -

Bindy Lambton was confined to a wheelchair for almost two years, which

probably laid the foundations for her arthritis and extreme lameness in

later life.

In 1966 she bought 58 Hamilton Terrace, a house suggestive of an Odeon

cinema built by Aunt Freda in the 1930s. Here Bindy installed a

butterfly-shaped swimming pool and created a beautiful garden. But the

family was never happy in this house.

Her marriage to Tony, perhaps under extreme pressure from the years of

infirmity, was beginning to disintegrate.

For a while it looked as if Bindy Lambton might follow in her mother's

footsteps, but her strength of character, unquenchable high spirits and zest

for life pulled her through, and she moved on to the final phase.

In 1970 her husband, who had succeeded as the 6th Earl of Durham, gave up

the peerage to retain his Commons seat. But two years later he resigned as

Under-Secretary for Defence in the Heath Government following a call-girl

scandal, and went to live in Italy.

Bindy Lambton moved to 213 Kings Road, formerly the home of her cousin

Pempie Reed. Here Bindy Lambton found a new lease of life, attracting

legions of friends and admirers from new generations: Shimi Lovat, Leigh

Bowery, Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall, and, most importantly of all, in her

later years, the musician Jools Holland and his entire big band.

She also became adept at deep sea diving, initiated into that dangerous

sport by the Olympic medallist, Vane Ivanovic. After watching her deep sea

diving off the Barrier Reef, the American conservative publicist, William F

Buckley jnr, wrote: "I have never met a braver man than Bindy Lambton acting

as bait for sharks."

In her last years, almost entirely blind and totally crippled, Bindy

Lambton's joie de vivre remained undimmed. So assiduous was her attendance

at Jools Holland's concerts that, at one point, he invited her in her

wheelchair to sit next to the guitarist on the stage at Newcastle City

Hall - for all the world as if she were a paid-up member of the band.

Although her attendances at Durham Cathedral services were less frequent,

these too could be notable. One recent Bishop is unlikely to forget how,

after an Easter Sunday service, Bindy Lambton followed him down the aisle in

her wheelchair, with headlights blazing, cheerfully proclaiming "Christ is

risen".

Bindy Lambton never wished to be thought of as "eccentric", for she always

strove to be - and imagined herself to be - a pillar of respectable society.

Her cheerfulness survived to the end.

In hospital on the day of her death, just before being given a morphine

injection, she amazed both the doctor and nurses by singing and acting out a

favourite 1940s song:

Cocaine Bill and Morphine Sue

Strolling down the avenue two by two.

O honey

Won't you have a little sniff on me,

have a sniff on me.

Those were her last words.

Friday, June 02, 2006

Why do Baptists Go to Heaven First

Why do Baptists Go to Heaven First?

"Because the Dead in Christ Shall Rise First".

Three Religious Truths

There are three religious truths:

1. Jews do not recognize Jesus as the Messiah.

2. Protestants do not recognize the Pope as the leader of the Christian faith.

3. Baptists do not recognize each other in the liquor store or at Hooters.

What Went Wrong With the War, Daddy

1 W MILSTEN: September 22 2002 19:41

| You would agree with this wouldn't you? If they are going to do it, I think they should do it like this and use Iraq as the seedbed of democratization in the Middle East. What do you think? US will rebuild Iraq as democracy, says Rice | ||||

| By James Harding and Richard Wolffe in Washington and James Blitz in London | ||||

| Published: September 22 2002 19:41 | Last Updated: September 22 2002 19:41 | ||||

The US will be "completely devoted" to the reconstruction of Iraq as a unified, democratic state in the event of a military strike that topples Saddam Hussein, said Condoleezza Rice, US national security adviser. As the White House has begun to consider military strategies in Iraq, Ms Rice said the US would seek a swift victory by using "sufficient force to win". Ms Rice, speaking in an interview with the Financial Times, signalled US willingness to spend time and money rebuilding Iraq after the fall of Mr Hussein's regime. Reinforcing the Bush administration's message that the values of freedom, democracy and free enterprise do not "stop at the edge of Islam", Ms Rice underlined US interest in the "democratisation or the march of freedom in the Muslim world". She said of reform in places such as Bahrain, Qatar and - "to a certain extent" - Jordan: "There are a lot of reformist elements. We want to be supportive of those." As the negotiations at the UN between US and British diplomats and their Russian and French counterparts are set to intensify this week, Ms Rice pressed the the security council for a clear resolution with effective measures of enforcement. Leaving open the possibility of sending weapons inspectors back into Iraq, Ms Rice said: "It will be important to try and determine, in some way, whether inspections have a chance. Inspections have to presume that there is going to be some co-operation on the part of the Iraqi government." Iraq said on Sunday it would not accept any new conditions on UN weapons inspectors. After a leadership meeting chaired by Mr Hussein, a spokesman ruled out additional conditions on inspectors following "press reports that US officials are trying to get the security council to issue new, bad resolutions". The Pentagon and Ms Rice's national security team are understood to have presented President George W. Bush with a number of military scenarios. Military planners are said to have emphasised the need for the application of overwhelming force - possibly involving air strikes at the same time as an invasion on the ground - to achieve a rapid victory. 2. I Predict Jan 27th as ATTACK DAY W Milsten That seems early to me. Rumors on TV are that Condaleeza told the UN inspections team not to plan for inspections in March so it is coming very soon. The outcome is not forseeable, but some things seem certain. Saudi Arabia's days as a Kingdom seem numbered. Israel has much to fear from this war. Turkey will give in to American demands to use Turkey as a launching site. 85% of Turks are against American forces in Turkey, but the Turkish Army is telling them it is okay and/or good and the population trusts their army. Tony Blair might lose his job (how would that work if the labour party wants him out?) What do you think. 3. MARCH !* 2003 [HOLT] OK, so this is how it will play out, Saddam will lob a few goofy little artilery shells with chemicals before their source gets wiped out by US bombing. The shells will have about as much effect as a couple of broken bottles of French perfume. In otherwords, they wont be any big deal. France will use this as a reason to join in with the US, and the US will praise their assistance "when it really counted" or something like that. This is how they will settle their little public rift. 4. Sent: ME: Friday, April 11, 2003 2:50 AM Funny, but it pisses me off when the suggestion is made that because one is opposed to war and imperialism, one is pro-Saddam! I am glad to see the fucker dead, although I would have preferred to have seen him tried before a court. Much more satisfactory, both for the victims and for history. I still think the aftermath is going to be awful. I will be glad to be proved wrong. PBH [But now its 2006, and I was proved right.] |

The Crusades are Overblown

In my opinion its useful to remember, in the current hoo-ha, the crusades have been vastly overemphasized in their general importance in European and world history.

Once you had gone over the various Eastern Mediterranean, Spanish, and Northern crusades, you tend to try to look at thematic issues such as the economy, art, architecture, music, law", the development of states, or intercultural relations." And this is where the problems begin.

That does not mean that as phenomena they did not intersect with developments in all these areas, but the were not, in my judgement essential to any given area. I'm far from the first to notice this - Donald Logan in his recent excellent textbook on the Medieval Church makes just the same point.

- The focuses of eastern Mediterranean trade were Constantinople and, above all, Alexandria. Until fairly late on these were not focuses of any crusade, and the crusades were only intermittent episodes in the pulse of trade.

- You may have got some mixing of Byzantine, Armenian and Western Art (Queen Melisende's Psalter, etc.) but there are very small number of such items, and such mixing occurred in Southern Italy as well.

- Intercultural relations: Sicily, Spain, Venice, etc, were all more important.

Thursday, June 01, 2006

Byzantines, Hellenes, Romans, or Greeks

One reads frequently that the Greek-speaking people of the Empire whose Capital city was "New Rome which is Called the City of Constantine" [the official name of the city until 1922 I think?], never used the word "Byzantine".

This is quite untrue - many Byzantine historians (Anna Comnena and Nicetas Choniates for instance) use "Byzantine" frequently, as any scan of their texts will show. It is true, however, that they never used "Byzantium" and "Byzantine" in the synecdochal way that modern Westerners do, but untrue that the word would be unfamiliar to them. By this I mean they used the term to refer to the city and inhabitants of Constantinople, not the entire East Roman realm.

In the 16th and 17tn centuries "Byzantine" becamse a useful word to refer to the Medieval Roman Empire in the East. [This was especially the case with the work of the great scholar Du Cange, who popularised the use of "Byzantine" when he was in fact talking about families from the city of Constantinople, a usuage well-justified by Byzantine sources.] The later and more general use of the word has long proved useful to just about everyone, Greek and non-Greek, since the Greek-speaking agricultural empire of the 7th century and later, with more or less only one major city for centuries after, was clearly distinct from the multi-civic-centered, multi-linguistic Roman Empire of antiquity. This is not to deny important formal continuities.

With the use of "Roman", which, I have to say, reminds me of the use of the word

"Anglo" by and about some distinctly non-English populations in Californian usage, it is true that this was the *normal* term used by Byzantine historians writing about their political history. I am unsure about how widespread that term would be in common usage - since Byzantine historians were rather too fond of archaic terminology to described various peoples ["Medes" and "Scythians" turn up, for God's sake!]. I do recall venturing into a Church in Istanbul in 1983 and greeting the custodian with some phrasebook Turkish, only to hear the thrilling response "No No, I am a Roman".

Then we come to "Hellene". There is no doubt that in normal Byzantine usage it meant "pagan". Since the continuity of Greek populations in almost *any* part of "mainland" Greece is extremely hard to prove, I am very unhappy with a suggestion that 17th century Greeks were "still" using "Helene". [And this is not just a matter of the famous 8th century Slavonic population movements, but the much later effects of plague and piracy - post 1347 accounts of the Morea, for instance, make it clear that thousands of Albanians were "imported" to farm empty land.]

"Hellene" seems only to have assumed a positive sense only under the influence of proto-nationalism. There were clearly some groups in the last centuries of Byzantium - Gemistus Plethon is the most famous representative - who tried to outline a distinct "Hellenic" identity. The mutual interaction between Greeks in Italy, where I presume "Hellene" received a boost from certain Renaissance schools of thought, and Greeks in Greece might also have had an effect. If sources for a 17th century use is "intellectual", then it might very well represent this late Byzantine approval of "hellene" rather than any "continuing" ancient use.

Some have argued that it is misleading to ever refer to the Eastern Roman Empire as Byzantine, with the claim that it is and an anachronism.

But the problem this is that there is not a single example*I know of where any

contemporary sources calls "the empire whose capital city was New Rome",

the "Eastern Roman Empire"!

Let's be careful in what we are suggesting is anachronistic here. And when it comes to terminology, as I pointed out above, the Byzantines (or at least the Byzantine historians) are the last people in the world who can insist on "politically correct" words. [Personally, however, I do not object to being called a "Frank"!]

How Long Should a Homily Be?

I've been going to church a lot recently. Mainly because I started helping at the St. Francis Soup Kitchen, and that put me back in touch with my original impression of Catholics as people who basically tried to do good things but without much sentimentality. In recent years the impression of old central Europeans saying bad things about gay men, while absolutely living the campest lives possible (it is just not possible to be butch and swing a thurible while wearing a lace surplice).

So now I face the big issue -

How long should a homily be?

I have noticed at various Catholic churches a tendency for sermons to get

longer and longer. Ten to twelve minutes used to be the norm: now twenty minutes can be getting away with it easily.

One of the problems, however, of having as many priests available to preach as there used to be, is that some preachers seem to loose self-control, and take the opportunity to preach, and an opportunity to go on and on for up to 25-minutes or half an hour.

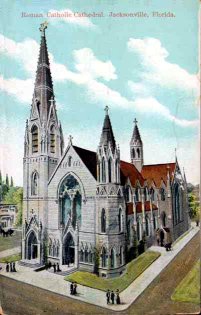

In reality this is a dumb thing to do, as a preacher an make a very good

impression in the first ten-twelve minutes and then alienate most of the congregation, by going on, and on, and on. Such preaching it seems to m, is a form of abuse of power. A problem in a Baptist town like Jacksonville, however, is that some of the worst offenders, and so now more an more seem to feel justified in subjecting us to Presbyterian-length sermons.

The problem is that , on the whole Catholics do not like this. Some argue

that if a preacher has wonderful things to say, they should take as long as

they need. I am sorry, but remarkably few preachers have such wonderful

things to say, and those that do can usually say it much faster.

On the other hand, if people come for the first time, and like the

community, the music, the ability to go to communion, and to let the body and eye pray as they taken in the church's art having to suffer through 25 minutes of "what my spirituality class over this past month", means might not come back.

Moreover, not all of us feel "spiritual;" all the time. Weekly mass

attendance might be all we do. Or we might go through periods of intense

spiritual evolution, and then dry patches. And many people -- the vast

majority -- are simply not called to be mystics, nor is this required by

the Church or any part of its tradition. In these cases, going to mass is

part of a regular "prayer of the body", but in needs to fit into a regular

schedule. If it helps in going to mass, that you expect it will take 1 hour

to 70 minutes, and then you go out with friends for a meal, there is

nothing wrong with that. If you come to mass late on Sunday, and then go

home because of work the next day, there is nothing wrong with that either.

But if all this becomes subject to the whim of long-winded preachers,

something gets upset.

Empires of the Word - by Nicholas Ostler

There has been a tendency to see such processes as almost accidental, but, while Ostler does agree that Empires spread languages, as do missionaries, he notes other, less obvious aspects. World languages that spread or overtake old languages which are similar to the old. Akkadian-Aramean-Arabic have all been the languages of great Empires, and all came to dominate the near-east. But even when the Persians conquered Babylonia, Assyria and Canaan, their Indo-European language did not spread. When the boot was on the other foot, Arabic spread everywhere in the old Akkadian/Aramaic world, but never took hold in Persia.

The book is full of similar provocations. If you liked the world-spanning view of Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel, you will probably like this. Slowly we are building up a library of truly global history books that are not just expanded western civ hack jobs.

There is an NPR show on the whole subject: NPR on Endangered Languages

[hat tip to Tony Marmo]

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Two Bulls

THe Young Bull says to the old Bull, "Let's run over there and fuck a cow."

The Old Bull says "let's walk over and fuck 'em all."

Yeats: The Second Coming

THE SECOND COMING

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

-- William Butler Yeats

Aquinas: Does he Prove God Exists? NO.

Fall 1987

Can Aquinas' Five Ways be Reclaimed from Medieval Cosmology?

"The hidden things of God can be clearly understood from the things has made"

- St. Paul

Romans I.20

"I shall show that neither on the one path, the empirical, nor on the other, the transcendental, can reason achieve anything, and that it stretches its wings in vain if it tries to soar beyond the world of sense by the mere power of speculation"

- Immanuel Kant

in Critique of Pure Reason

(A591/B619)

Introduction

St. Thomas Aquinas' Five Ways are often considered as the most convincing set of proofs for the existence of God that there are. On examination they seem to be so tied to an outdated cosmology that they are not capable of being accepted by anyone acquainted with modern science. I propose in this paper to look at each of St. Thomas' arguments and its cosmological background. I shall try to see if the arguments work in a universe shaped by modern physics . It must be said immediately that there is a problem in identifying St. Thomas' arguments with their modern transpositions, but it is one worth living with because of the intrinsic interest of St. Thomas' approach; that we can come to know the existence of God from our observation of the world. This is an approach based on Pauline ideas , and one that became Catholic orthodoxy at Vatican I . Modern philosophy has used up a lot of effort discussing the epistemology of science, but serious philosophers have not so far come to terms with the possible metaphysics arising from the content of modern physics. There are good, perhaps insurmountable, reasons for this failure, but, if such a metaphysics can be described, St. Thomas' thinking is a good starting point. After some general considerations, I shall look at each of the Ways in turn and finally consider whether they can point the way for a present day natural theologian.

I General Considerations

It will be seen in this paper that Aquinas' five ways are all based on using observed `facts' about the world to argue for the existence of a god. This whole procedure has come under close philosophical scrutiny. It has suffered both from the onslaught of Popper's views on falsifiability, if we take it as a purportedly scientific argument, and Kant's whole attack on natural theology . As Kenny has pointed out falsifiability does not apply to the concept of God because of the nature of the concept. Kant's arguments, which I will consider more closely, also do not seem to be directed against Aquinas' arguments.

It was Kant who first issued a decisive challenge to natural theology . He divided arguments for God into three types, the ontological, based on a priori reason alone and familiar from Anselm and Descartes, cosmological , based on the existence of anything at all rather than any empirical facts, as seemingly exemplarised by Leibniz, and physico-theological arguments, based on facts about the world and most famously illustrated in St. Thomas' Five ways. Kant's procedure was to invalidate the ontological argument by trying to prove that forming a concept in the mind is different from instantiating it . He then tried, fairly successfully, to show that the cosmological argument reduced to the ontological one. He was more favourable to the physico-theological argument but held that it only proved an architect , not a creator and did not give "apodictic certainty" about that. To go further Kant felt it had to fall back on the ontological argument which he held to be invalid. Kant was not an atheist and had his own `moral' necessity for God. His whole stress was on restricting reason to the realm of the senses. If Aquinas is to be defended, not only must we try to extract him from antiquated science, but we must also try to face Kant's powerful objections to going beyond the realm of the senses. We must in short consider the validity and nature of claims we can make of scientific `facts' and the sort of knowledge they give us.

Science has moved on from the time of Kant as well as from the time of Aquinas, and it may be the case that Kant's challenge, great as it was, is outmoded, for physicists now do go beyond the world of the senses.

Aquinas' arguments are based on observations about the nature of the world, in other words on science. If we are trying to construct arguments for the existence of God that are logically compelling in the same way as mathematical proofs, and this seems to be the aim of natural theology, then it is essential to know just how much one can trust scientific knowledge. The whole problem of induction has led to problems with the idea that the purpose of science is to unshroud built-in laws of the Universe. Karl Popper's views are one widely received response to this idea. Popper's insight is that science is not actually about discovering "laws of nature", rather that it posits a model of the world to be amended by later criticism: the model is good only as long as it works. The striking point about Popper's conception of science is that even if theoreticians actually came up with a model of reality that was perfectly matched to the Universe, no-one could ever know more than that it was the best model so far. In other words no secure knowledge is possible from science on which to build, for instance, a proof for God's existence . This view creates real problems for Aquinas' method. If knowledge about the world from empirical investigation is in fact insecure then science does not provide a very good basis for physico-theological arguments . however, the situation is not quite as bad as this might suggest. Popper's arguments are mainly concerned with what happens at the edge of scientific knowledge. It does seem possible to say that, now, the central core of scientific knowledge is secure and future models will not negate it . It might be possible, even with a Popperian view of science, to essay an argument for God's existence that is as credible as modern science, in other words an argument which although not ultimately conclusive is as compelling as the particular cosmology proposed by science at any particular point .

Physico-theological arguments always depend on some cosmology. Plato and Aristotle both shared the Greek view that the world was eternal and put forward their views of God with that in mind. Medieval science, such as it was, tended to be drawn from what had been read in the surviving works of Plato and Aristotle, observations made by Roman authors, and compendia such as those by Isidore of Seville - all mediated through the central Christian belief in the Creation drawn from Genesis. The Empedoclean idea of four elements , composed in turn by combinations of hot and cold, wet and dry , furnished the basic concepts of matter, and alchemy, and Ptolemy provided astronomy, and astrology. Medieval science was based on authority rather than observation; as such it formed a particularly insecure foundation for St. Thomas' arguments. Even if his approach works the raw data has to be amended.

Modern understanding of the world, pace Popper, is much deeper than the medieval conception. Modern cosmology is in one respect less unified than the medieval version. Then everybody at least thought their views made sense. 20th century physicists have long had the problem that their two best models of reality, in terms of results, directly contradict each other. The General Theory of Relativity cannot be true if Quantum Mechanics is true . Although many physicists believe that a Grand Unified Theory (GUT) is possible, no-one has demonstrated one. Does this mean even a limited proof of God's existence tied to our modern cosmology is impossible, on the grounds that we do not in fact have such a cosmology in modern science? Or that Aquinas cannot be modernised since we have no coherent cosmology in which to set his work? What we can say is that over their areas of application both general relativity and quantum mechanics do work and might yield some useful theological information. Secondly that modern physics does have seminal ideas which unite disparate theories; for instance the idea of simplicity, and the idea that the universe is logical .

With what we do have in modern physics I shall now examine Aquinas' arguments and investigate whether they can be expressed in a way convincing to modern ears.

II An Overview of Aquinas

St. Thomas was working in an established tradition when he proposed his Five Ways. His sources as a philosopher, his Greek and Arab predecessors, had been concerned with proving God's existence. his Five Ways can be seen as being based on Aristotle's' doctrine of four causes . More recently St.ÿAnselm had originated the ontological argument, which Aquinas rejects with some regret. Aquinas himself had given some of the arguments earlier and at greater length . Proving God's existence was something important both in the theological tradition he was working in, and to his own project of reconciling the Christian Faith with rational philosophy.

As McDermott points out the first lines of each Way refer to experience. The Five Ways are attempts to show how human belief arises in the normal course of events. This was St.ÿThomas' chosen ground. His procedure in all the Ways was to argue from effect to cause: his basic argument has been characterised as follows :

i) from experience we know that things are changed(I), dependent(II), temporal and contingent(III), limited(IV), and directed (V).

ii)these "effects" imply something else.

iii) Something which is unchanged, independent, eternal/necessary, unlimited and not directed.

iv) This is God.

As stated these arguments would, if they all worked, fill out the notion of a God who, if not quite Christian, fits many of the criteria of the God of Faith.

III The First Way

The argument of the First Way is based on Aquinas' analysis of the nature of movement or change (motus) . The experiential basis is the fact of movement/change . Using his concepts of potentiality and actuality he tries to show that a thing in the process of change cannot be both changing and itself causing that change. In this way a regression of movers/changers is established. Aquinas' premise here is that in any series to have a last member there must be first member. It is clear from Aquinas' analysis of change that the populist version of this argument - that there cannot be an infinite regression in time - is not what Aquinas had in mind. Aquinas had no difficulty with the idea of an everlasting universe that was also created . He is arguing rather that what is moving/being moved has to have an explanation of why it is moving/continuing to move at the precise moment it is moving; as Gilby puts it St. Thomas is arguing for a rising level of explanation at the moment of movement/change.

There are many problems with this argument, both logical and scientific. Most alarming is the use of the quantifier shift fallacy : the argument that the statement "for all values of x there is some thing y such that x bears the relationship F to y" leads to the statement "there is one y such that for all values of x, x bears relationship F to y". St. Thomas seems to be arguing from "secondary movers(x) do not move(F) unless moved by a first mover(y)" to "there is one first mover(y) that moves(F) all things(x)" . In other words even if St. Thomas' argument can be made to work scientifically it is not at all clear that it would lead to one first cause, whom we could call God. Kenny has also pointed out other problems; in particular, if Aquinas is really only concerned with movement at one instance, how does he account for causation within time and how does his argument prove that an unmoved mover does not move at other times. On the other hand, even if Aquinas' conclusions do not hold up, his appeal to the impossibility of infinite regression has been upheld by Salamucha , who maintains that while Aquinas' rejection of infinite regression is based on the idea that an infinite set must be non-limited from at least one side, an idea rejected by modern set theory, this same idea can be accepted in the real world .

The scientific basis of the argument was Aristotle's physics . Aquinas, following Aristotle, held that there was no such thing as action at a distance: anything moving was being moved by something . Aquinas held this despite the availability of an impetus theory of movement at his time . This "contiguism" was required if Aquinas was to insist that the thing moved was being moved by its first mover instantaneously. Kenny has argued that even in the terms of medieval physics Aquinas would have found it difficult to argue that every moving thing was being moved physically by God: the activity of an animal or even an arrow in flight contradict his premise. It would seem that in Way I, quite apart from its logical difficulties, Aquinas is tethered to a scientific theory of motion/change which does not support his argument, even if that theory were true.

Modern physics would seem to have dealt the argument an even more telling blow. Newton's First Law of Thermodynamics , which in itself does not account for the origin of motion , wrecks the ideas of contiguism and so of simultaneous action. The whole Newtonian concept of forces seems to assert that action at a distance is possible; the "luminferous ether" was never found by later researchers . Some have denied Aquinas meant local motion, but the examples of motus given by Aquinas show that he meant exactly that. Newton, however, is not the last word in physics. Aspects of Einstein's uniting of inertia and gravitation, as well as his concept of "fields" , seem to have restored some respectability to the idea that motion has a direct and sustained cause. These causes of motion however, are mutual and would not provide good arguments for a first mover. The same goes for the notion of "virtual particles" and the other particles that sub-atomic physics sees as being constantly exchanged to explain the action of forces .

The First Way then seems not to work in the science of St. Thomas' day, nor to be salvageable in terms of modern physics if the idea of an instantaneous series of movers for any motion/change is taken as central to the proof. One other approach may be open. An argument based on the observation of motion/change in the Universe may work if it is set within time. If the motion of all large bodies is seen as the composite motion of all the sub-atomic particles that compose them, then it may be possible to argue that there is a series of temporal causes of movement of all such particles going back through time. It would be possible for such a regress to be conceptually infinite but actually limited by the modern conviction that the universe did indeed have a beginning. One could argue there would have to have been some "first cause" of all motion at the zero point. An argument in this form is far from Aquinas' more subtle notion of an instantaneous regression of movers, and closer to the popular idea of his argument. This argument also runs into problems. It only allows for material causes, whereas, for those who believe in freewill, consciousness or spirit has some effect on matter, so precluding the idea that all chains of causes go back to the Beginning. More problematical still is that quantum mechanics destroys the classical determinism on which such an argument rests: it seems to be the case that there is no immediate physical reason why an alpha-particle, for instance, should veer one way or the other even if statistically the spread of many alpha-particles is predictable . As was indicated earlier the science involved here is at the edge of current knowledge; it is not secure enough to prove God.

The argument from the experience of motion/change does not seem to work. Attempts to salvage it are problematic to say the least. Although Aquinas thought this was the "most obvious" it cannot be held to compel belief.

IV The Second Way

With the second Way Aquinas takes our experience of things being caused to argue for God . The argument is similar to the First Way and concludes that there must be a first cause because without a first cause there can be no intermediate cause and so no effect. Since there are effects (the world around us) there must be a first cause, who is God. Once again Aquinas seems to be talking about a series of immediate causes, rather than any series through time . Aquinas does not argue that everything is caused, accidents do occur , but if at least somethings are caused in the way he argues then he thinks his argument works.

Gilby accepts the immediacy of causation but argues that the causes in question are meant to be metaphysical, and that the point of the argument is that something outside an effect causes it, and so there must be something, God, who is outside, and causing, the Universe. For Gilby it is the fact that St. Thomas is talking about an essential subordination of causes rather than an accidental (and therefore temporal) subordination which indicates the immediacy of the causation . The problem with Gilby's view is that, if Aquinas is not referring to scientific/natural causation, it is hard to see how he can be arguing that our awareness of metaphysical causation comes from our senses. The argument loses its force. Kenny accepts that Aquinas is talking about an ordered series of increasingly higher causes but ties this in to Aquinas' view of the reality of the effects of heavenly bodies. In his view the Second Way is tied to an astrological cosmology.

Before going on to consider the cosmological issue it is perhaps worth taking a look at the issue of infinite causal regression. Aquinas had used the supposed impossibility of infinite causal regression in the First Way, here equally it is at the core of the argument. Brown has gone into the whole issue in some detail. He points out that it is sometimes thought that Aquinas believed infinite regression was impossible due to the impossibility of infinite simultaneity of causes . Brown's view is that Aquinas was quite aware of the mathematics of infinite regression but that what he was concerned about was the "explaining value" of causes. For Aquinas it is not sufficient to say that "x causes a" is satisfied by "there are an infinite series of causes for a". For effects to be intelligible there must be an explanation and so a first cause . His rejection of infinite causal regression then would be based on the metaphysical need for an explanation. This ties in with Gilby's view of the argument. If Gilby is correct, then Brown shows that as a metaphysical argument the Second Way might work in logic. However, as has been said, it would then lack the compulsion of an argument based on observed reality. Furthermore, as we shall see, Kenny does seem to show that Aquinas' idea of causes was more physical than Gilby will allow.

There are both logical and scientific problems with this Second Way. The old chestnut that Aquinas argues everything must have a cause, and then postulates an uncaused cause, is not easily avoided. There is once again a problem with a quantifier shift in the argument: here it runs

"effects(x) are not caused(F) unless caused by a first cause(y)" to "there is one first cause(y) that causes(F) every effect(x)".

The scientific problems are attached to the cosmology within which Aquinas saw his hierarchy of causes working. Aquinas, like many medieval intellectuals, accepted the astrological idea that the movements of the heavenly bodies effected people on earth . The movements of the spheres effected, as intermediaries between God and His/Her creatures, the wills of people on Earth: a parent begetting a child might be seen as being influenced by the Sun. Unlike the variations in physicists' estimate of the nature of motion, astrology has no modern defenders in the scientific world . On a more mundane level the whole notion of causation is uncertain if quantum mechanics properly describes the world .

At first sight the Second Way seems to be more defensible than the First. It seems less linked to a particular cosmology. Further investigation shows that this is not the case. The argument is either an argument for a metaphysical hierarchy of causes, in which case it has no real connection with the physical experience which makes the Five Ways so persuasive, or it is attached to a view of astronomy which has no force at all. Any recovery of the argument would go along the lines given above for the First Way, and would run into the same problems.

V The Third Way

The Third Way is again based on an observation of the real world , this time the process of generation and corruption. It is not then, one of Kant's "cosmological" arguments . This argument is one of the most interesting of the Five Ways and perhaps more than any other can be made persuasive. Aquinas' argument is that if all things are corruptible, at some time in the past all things would have corrupted and so there would be nothing now. Since there is something now, it is necessary to accept that there are some necessary beings. He then sets up an infinite regression of necessary beings, a regression which he rejects on the same grounds as in the two earlier ways. His argument is from contingent beings to necessary beings to uncaused necessary beings . As stated this argument again involves a quantifier shift , and Aquinas does not explain why the fact that all things are corruptible means that at one point all things must be corrupted. However, unlike the earlier arguments this starts out from a premise (the generation and corruptibility of things) which seems to be true in modern science .

The issue of what Aquinas meant by "necessary being" has been raised by Brown . It is clear that Aquinas thought created things could be "necessary" in the sense that they are not subject in the natural way of things to corruption. One point to note here is that Kant specifically attacked arguments from contingency on the ground that they reduced to the ontological argument by making the postulated necessary being a perfect being. Aquinas' necessary beings are not perfect and the argument is more physically based than Kant's target.

The problems with the Third Way are not then to do with Aquinas' physics. The real problem is with Aquinas' view that if there are only corruptible things then at some past time everything would already have corrupted . He had no real grounds for saying this, since he was determined not to insist that the Universe had a starting point in time. The general idea seems to be that in infinite time all possibilities would be realised. If one of these possibilities is that all things would have corrupted, which is indeed a possibility if all things are corruptible, then at some time in the infinite past this eventuality would have already been realised . This idea is simply not provable: there seems to be no reason why contingent beings cannot be kept in existence by other contingent beings, and the world as we experience it is full of unrealised possibilities every time a choice is made. Aquinas is hung by his own petard here in keeping to the assumption that the Universe is infinitely old.

Newtonian physics and Big Bang cosmology would seem to give more to Aquinas than Aristotelean physics. After all "if one could establish that the material world has not always existed, then the principle that no substance can begin to exist without a cause would provide a swift proof of a creator" . The principle "that no substance can exist without a cause" is not proven nor disproven , but seems at least intuitively likely. Newton's Second Law of Thermodynamics , if true, implies that the entropy of the Universe is continually increasing. Since Einstein showed matter and energy are convertible, at some time all mass in the Universe will be either inert or converted into energy and that energy will be equally distributed: total entropy will have been reached and the Universe will have reached its Heat Death. Since the Heat Death has not yet occurred, it would seem to be the case that past time is not infinite and that the Universe has a beginning. Adair points out that such a scenario depends on the Second Law working at all time and in all places: "actually our knowledge of cosmology...is much too incomplete to regard such a hypothesis [Heat Death] as more than an amusing fancy". For the time being, pace Adair, Newtonian physics would seem to indicate a beginning of the Universe and so give Aquinas' principle in the third Way support he could not have imagined. Even if Newton's Second Law is eventually falsified, the Big Bang theory of the Universe's origin also supports the idea that the material world has not always existed. Although Adair avers that we have no absolute proof of the invariance of the Universe, he is prepared, using a principle of invariance, to go back over 15 billion years to the first tenth of a second of the Universe's life . He thinks there was a zero point but says "we do not know what time zero means" . Even if there was a beginning of this Universe, there is no way of knowing absolutely that what we call time zero had nothing before it . As modern science stands however, it seems reasonable to think that the material world did "come into being". As such the principle involved in the Third Way would lead to a creator or creators.

The argument put forward here is not the same as the Third Way but it does use the principles Aquinas proposes. There are too many uncertainties with the science involved to claim that such an argument is compelling, but, given what we think we know about the Universe, it does have a certain fascination.

VI The Fourth Way

The basic contention of the Fourth Way is that whatever is most F must be the cause of all else that is F, therefore since we know there are good things and existing things there must be something which is most good and most existing and this we call God. The data of experience appealled to is our everyday experience of the gradation in things. This argument is clearly platonic and is the argument most in tune with the Christian Neoplatonism that had prevailed until the 13th century.

The argument of the Fourth Way depends on the truth of a Platonic ontology. In contrast to Plato's concern with the eternal aspect of Forms - for Plato the world of Forms simply describes how things are - Aquinas stresses that the highest good causes lesser goods. This goes along with Aquinas' overall emphasis on creation. A basically Platonic world is assumed however, and so the argument runs into all the problems of Plato's cosmology. Kenny lists modern attempts to re-conceptualise forms; "paradigms", such as the standard metre in Paris, "concrete universals" such as "all the water in the Universe", "concepts", and "classes". All these have similarities with Platonic Forms, but they fail in one way or another to satisfy what a Form was meant to be. Plato's Forms were to fulfil the role of both universals and paradigms: it is impossible however, for one thing to fulfil both roles. The objections to Platonic forms make that part of the Fourth Way which suggests that a thing's Fness is caused by some supremeÿF difficult to defend. As well as this fundamental objection there are problems as Kenny notes with the whole idea of gradation: to what extent can perceived gradations be attributed to the things themselves rather than to the prejudices of the observer?

The Fourth Way is perhaps more attached to a cosmology which cannot be updated than any of the other Ways. There are still unsolved problems to do with the nature of universals. Any solution is not likely to come from physics as the problem is essentially meta-physical. If the force of physico-theological arguments comes from their base in experience, then a non-experienced metaphysical understanding of universals, if one be possible, is not going to result in an argument for the existence of God with the same persuasiveness. Unless one already accepts a Platonic ontology as read, this Way offers little to persuade the sceptic.

VII The Fifth Way

The Fifth Way , the argument from design , again argues from human observation and is probably the most popular of St. Thomas' Ways. Oddly enough the Fifth Way differs from the popular argument from design in not insisting that everything is designed, Aquinas only insists that the actions of inanimate objects show design , and in not insisting that the design is good, an issue he deals with elsewhere . In the Fifth Way it is activities with goals that are in question rather than the idea that things as a whole are designed: as Gilby observes Aquinas did not have to explain why God made mosquitos. Aquinas' argument is that, if non-conscious agents do tend to a goal, then something outside them must be directing them. For nature as a whole the only candidate is a being we would call God.

This argument goes very well with Kant's insistence that only an architect of the world could be shown to exist - Aquinas does not here insist on God as creator. still, all is not straightforward for Aquinas. Kenny finds a real problem in Aquinas' claim that all adaptive or goal directed behaviour indicates intelligence. The implication that there is only one designer also seems to be the result of another use of a quantifier shift . Because Aquinas argues from the actions of individual things he has no real way of claiming that they must all have the same end or same designer. His argument seems to be weaker than the more traditional argument that the whole Universe exhibits a design: in that version several designers may have been involved, but that there is only one design for the whole cosmos makes a single designer more credible than with Aquinas' version. Why then is Aquinas arguing from the directedness of individual things and not the design of the Universe as a whole, an argument he did know about? One must assume that he felt there was some advantage. In a less optimistic age he might have felt it was less than persuasive to suggest that the Universe was all good. Also by choosing this way, he avoided arguments about why a designer would have designed faults in the universe. Whatever the reason it is clear that Aquinas' argument as given is less compelling than the more traditional argument from design.

It is perhaps still worth looking at this common argument from design. Even if we deal with the this version, there is the problem that the whole argument rests on an aÿpriori principle of causation . Nevertheless modern physics would tend to support an argument from design as much as any previous conceptions of the universe.

As has already been noted , modern physicists have a predisposition to see the Universe as logical and simple. This indicates some sort of order or design. The instantaneous exchange of information between particles that seems to make statistical prediction in quantum mechanics possible could also support the notion of an underlying unity and design in the Universe. The great problem for the Greeks - how could something come from nothing - also seems less difficult than before; it has been suggested that the total energy of the universe when all additions and subtractions are made is zero. it may actually have cost no energy to make the Universe . Here we are at the bounds of modern physics , but interesting possibilities are raised when one is considering just how a creator/designer could operate. Even more potent is discussion of the so-called anthropic principle . The chances of the Universe being right for life now seem to be very small indeed. Adair thinks the possibility of life away from the Earth may be to small to consider; we may be alone. The exact values of the speed of light, the strength of the nuclear weak force, and other physical constants all seem to be just right for human life. If modern physicists are correct in their estimate of what went on in the first few seconds of the Universe's life than all these values were set in the totally unpredictable breakdown of the original symmetries in things which occurred in the first few milliseconds . Even the time we are on Earth might be seen as ordained; the Universe is expanding and in a billion years' time matter will be 15% more tenuous than now . It is not clear what effects, if any, this has on the nature of life. Some of these ideas are not as yet proven, but such as they are they would provide strong arguments for any modern setting forth of a design argument. In some respects however, the argument from design is hardly touched by developments in science. A newtonian generation could have found similar evidence of design, as could a earlier believers in the Ptolemaic astronomy. It is the whole notion of there being order rather than chaos which gives the argument its strength. A point to note however is that Kant objected to reason going beyond the bounds of the senses; in modern, as compared to classical, physics that is exactly what is now being done to try to grapple with the nature of things. Kant may have been reflecting Enlightenment prejudice about the limits of rational inquiry.

The Fifth Way as proposed in the Summa has problems in the structure of the argument and in Aquinas' concentration on the directedness of individual activities. The problems are related to the argumentation itself rather than, as with some of the other ways, the scientific background. St. Thomas himself elsewhere argued for a more global idea of design and his intuition that design in the world provides grounds for the existence of a deity is still one that is full of potency, as the speculations on modern cosmology have indicated. The Fifth Way, along with the Third, would, in modern guise, seem to be the most persuasive of St. Thomas' approaches.

Conclusions

This paper has taken an unorthodox approach to Aquinas' Five Ways. That the arguments do not work as they stand is clear. The logical difficulties of the arguments alone ensure that. Indeed it is surprising to find a mind like Aquinas' repeatedly using a quantifier shift to make his point. The cosmological background has also been shown to make some of the Ways untenable to a modern reader. However, St. Thomas' approach has great value in that arguments from experience seem to be the most persuasive. Two of the arguments, when taken together, seem to me to be quite powerful. The Third Way and the principle that nothing can cause itself, seems to imply some sort of creator if the Universe indeed has an empirical beginning, which at the moment looks likely. The basic intuition in the Fifth Way that order implies a designer also seems to have some force. Kant would allow that order may indeed indicate a designer and he had no way of knowing that the Universe was not everlasting. Together, the principles in the Third and Fifth way would lead to some sort of creator and designer, or a plurality thereof. This would not amount to a proof of the Christian God, but if one can show divinity exists at all, other arguments are then available to describe it. The problem is, as indicated earlier, that the science we might base physico-theological arguments on is insecure, and if Popper is right it will always remain so. If that is the case, then the ontological argument may indeed be the only philosophic proof available. In spite of Vatican I, modern Catholics have joined their protestant co-religionists** in turning away from proofs of God to fideism . Aquinas would surely agree on the value of Faith and religious experience: but not totally. the invigorating thing about St. Thomas is that he was convinced of the power of human reason, something upheld at Vatican I and a mainstay of Christian freedom. His thought, adopted as Church teaching, provides a bulwark of rationality in an institution which often seems to act without any.

Bibliography

St. Thomas Aquinas: Summa Theologiae (Blackfriars/Eyre and Spottiswode) London 1964 - references ST.(part).(question).(article).(reply)

: Summa Contra Gentiles (various translators, Vol I by A.C Pegis) (University of Notre Dame Press) Notre Dame 1975 (First published as The Truth of the Catholic Faith by Hanover House (pub) 1955)

Modern Works

Adair, R.K. : The Great Design: Particles, Fields and Creation (Oxford U.P.) New York 1987

Aquinas: A Collection of Critical Essays ed. A. Kenny (Anchor Books) Garden City, New York 1969 - (individual articles listed separately)

Brown, P : "Infinite Causal Regression" in Philosophical Review 75 (1966) pp. 510-525 (also in Aquinas ed. Kenny pp. 214-236)

: "St. Thomas' Doctrine of Necessary Being" in Aquinas ed. Kenny pp. 157-174 (originally in Philosophical Review 73 (1964) pp. 76-90)

Kant, I : Critique of Pure Reason 1781 trans. F. M. Mueller (Anchor Books) Garden City,N.Y. 1966 (1st edition of translation 1881)

Kenny, A : The Five Ways (Univ. of Notre Dame Press) Notre Dame, Indiana 1980 (first published (Routledge & Kegan Paul) London 1969)

Kovach F.J. : "Action at a Distance in St. Thomas Aquinas" in Thomistic Papers II ed. L.A. Kennedy & J.C. Marler (Center for Thomistic Studies) Houston, TX 1976

Popper, K.R. : Popper: Selections ed. D. Miller (Princeton U.P.) Princeton 1985 (previously published as A Pocket Popper (Fontana) London 1983)

Salamucha, J : "The Proof Ex Motu for the Existence of God: Logical Analysis of St. Thomas' Arguments" in Aquinas ed. Kenny pp. 157-174 (originally in. New Scholasticism 32 (1958) pp. 334-372)

Strawson P.F. : The Bounds of Sense (Methuen) London 1982 (first edition 1966)

OUTLINE USED FOR THIS PAPER

Introduction

A. What paper will look at

a. Thomas args - w/o going into detail of each

b. is there a modern world view in which they

could be said to work

1. If I reinterp T's args , are they the

same

c. Vatican I and St. Paul

d. Aquinas' cosmology

e. Modern cosmology

1. failure of mod philosophers to come to

terms with poss metaphysics of content of

sci cf their concentration on Epist of Sci

I. General Considerations

A. Procedure of using facts about world to prove God's existence

a. Kenny and Kant

b. Kants division of args for God

1. Ontological

2. Cosmological - Leibniz reduces to Ontological

3. Physico-Theological

c. Kant's problem with these

1. advancing beyond world of senses

a. applies to mod physics

2. using universal causal dependance to get a

first cause outside system

3. We are left with no picture of God

4. PhysTheol only shows an architect

a. sees these args as re Order

this is not Aqs arg in Way 5

b. nb such an architect would satisfy many

d. Kant's challenge is great but outmoded for phyiscists

do go way beyongd world of sense. Also his args are not

directed vs the ones Aq gives

B. Nature of Scientific Knowledge

a. How secure is Scientific Knowledge

b. Problem of Induction

c. Karl Popper's view -good

1. Relation to Aquinas Procedure

a. if knowledge about the world from

empirical investigation is at all

insecure it does not provide proof.

2. Invalidates all pys-theol args but not ontol.

C. Physico-Theological Arguments dependent on a particular

cosmology

a. eg Aristotle/Plato

b. eg Medieval Philosophy - what is it

c. eg Newton

D. Cosmology at the moment

a. Popper - no certain Cos. thfr no poss proof for God

b. Incoherence of present Gen Theory of Relitivity

with Quantum Mechanics

1. nb there is general agreement on possibility

of GUT

c. Does this mean no de facto cosmol. arg poss

1. no cosmology thfr no cos. arg

2. does this mean AQ cannot be modernised, since

we have no actual cosmology to modernise into.

d. But Modern Cosmology/Physics does have Seminal Ideas

1. Simplicity (cf Nplatism)

2. Unity of fields - cf Adair

3. Nature of claims of modern physics

e. Physics also throws some light on Aqs. args

which might save them

II. Aquinas

A. Tradition - Greeks + Arabs

a. 5 Ways can be seen as based on Aristotles

four causes

b. He also argues elsewhere

1. ScG

c. Rejects Ontol arg Ia 2.1.2.ad2

B. Aquinas World View

a. See Card

C. What he was trying to do

a. Serious Arg

b. They fill out meaning of God

c. make things explicable

D. Procedure to argue form effect to cause

a. applies in all args

E. Standard form of arg - given Kenny p37-8

F. Quantifier shift fallacy at end of 1,2,3,& 5

II. First Way

A. Question of Movement

a. The Argument

1. basically no first cause no final effect

a. Inf Causal Reg

b. Gilbey - a rising level of expalnation

2. Not Going back in Time but NOW

a. Aq accepts possibility of eternal

world

3. argues for explanation req for continuity in

change

b. Problems

1. use of quantifier shift in arg

a. no reason for only one First Cause

2. Kenny - confusion over moveri

3. Aristotelian Physics

a. Contiguity of motion cf action at

a distance

b. impetus theory was available

4. If instantaneous no causes through time

c. Newton - First Law - Inertia

1. does not a/c for motion, but gets rid of

contiguity + simulataneous action. ditto so

does speed of light

2. Some deny motus is Local motion - but Aq

did mean this.

3. In any event later sci. negs this arg

d. Einstain anf after - gets rid of action at a

distance. But Gravity is mutual - no chains of

movers

e. Post Einstein - sub atomic quarks + gluons and

smaller.

f. Solution

1. see above

2. If aq did make it a regress in time of

all sub-atomic particles - to big-bang

3. Problem is Uncertainty principle and q. of

causation.

IV. Second Way

A. Question of Cause

a. A series of causes must stop somewhere

1. Gilbey - Metaphysical not scientific causes

but then arg loses force

2. View of the Cause being physical as opposed

to an event

3. Simultanity again

b. same as Way I in ICR but less about movt than

actaul causes - aim to prove not beginner but

a sustainer

1. ICR Brown - Meta 994a2-19

Aq thought an inf series could not have

both beg and end - it can eg 1-2

2. Brown - its sometimes thought ICR is per se

imp due to imposs of infinite simulatainty

but arg here is about need for a first member

not length of series ???

3. aq rejecta ICR as he wants an explication

c. Problems

1. Arg still contradictory even if it does not

go back in time - argues for anu uncaused

causer while saying all is caused

2. Use of quantifier shift

3. Aristotles Physics

a. four types of cause Mat Form Eff Final

4. Eudoxus' astronomy

a. movement of speres affecting earth

b. Kenny on this p 43-44

5. Doesn't simultainity leave temporal cause

to be considered like Islamic atomism

6. Heisenbergs Uncertainty principle

a. state it (on card) 1927

b. Quant Mech in general

þ. God playing Dice

c. Doesnt effect large scale

d. BUT PARTICLES ARE FUNDAMENTALLY RANDOM

7. Solutions

a. Aq does not insist all has a cause, we

can argue that it does

b. And that ICR is imp due to big bang

c. but this is less deep than AQ,and a diff

sense of cause - in fact more like design

V. Third Way

A. Question of possibility and contingency

a. Based on generation and corruption observed thfr

not a Kantian Cosmo arg

1. View of necessary being

a. an incorruptible being - so Kants args don't work

here

b. Point of Way II is that cont. beeings have built-in

corruption.

c. Sub atomic particple might now stand for ness beings

-(NO - see Adair - Ness beings without true ID not

thinkable)

b. Arg given in Scg I 15 5 for God's eternity

c. Problems

1. Is ii possible to argue from contigency

to actuality

2. Problem with whole idea of if everything, not

ness then once nothing.

-user quantifier shift again (see Kenny p 56

-poss epicurean bkgnd ?

-Aristotles view that if something can happen it

does - so Aq's arg is a red. ad adbsurdum

-here Aq's view of universe as eternal hinders

him

a. use quote - Kenny 66 - if mat world has not

always existed then .... Creator"

3. Does not point to one only ness being

a. use of quantifier shift

d. Solution

1. Newtonian Physics/entropy

a. Entropy in infinite time means now

wld be Heat Death - although Adair

disagrees

2. Einsteinian Physics

3. Nb in modern physics all we can say is the

present universe had a zero point, but we can not

know if there was nothing before. This would seem

to give a lot to Aq.

(TIE IN WITH KANTS ALLOWANCE OF AN ARCHITECT FROM

TELEOLOGY AND YOU MAY HAVE A PRETTY GOOD PROOF)

VI. Fourth Way

A. Degrees of Perfection

a. Based on gradiation observed

b. Only Perfect F is truly F thfr only God is true being

1. God here = Plato's form of the Good

c. Base is Platonic Ideas - needs Platonic ontology to work.

1. Gilbey gives refs

2. Aq stresses causal dependance

3. Aq not in fact a beliver in Forms - but nb,

Aristotle refers to `eidos'=form

4. Kenny discusses God as his own essence here - no need

for me to - but points out esse is a thin predicate

d. Solution

1. no - but nb problem of universals still unsolved

-not evrything is a matter of physics

2. but q. do modern physical constants have links with

Ideas. Probably not

-Concrete Universals

Paradigms

Concepts

Classes (most like forms cf Russells Paradox & 3rd man

-none are forms

II. Fifth Way

A. Argument from design

a. Based on none sentient beings actions - not on order

of universe. ie individuals action not cosmic order

1. calls for explanation

2. He has to show agents work for ends - Kenny, not very

strongly doubts this.

3. Use of faults in nature to prove it - eg monsterous

births

4. Aqs arg is not a God of the Gaps one

b. most promising arg - Kant thought it shows an Architect,

although he did not think matter could be created

c. Kenny has questions about whole q. of regular beneficial

operations and their interpreations

d. Uses Quantifier shift again

1. because Aq argues from actions of individual beings

there is no way of saying they must all go to one

end - so this is less strong than more trad design

arg , which he does give elsewhere (SCG III.3),

which does not demand one end but seems more

to indicate it

2. He presumably saw some advantage if refering to

non-sent beings - what ?

e. uses analogy of human design cf world

f. Gilbey - says it is to be read in light of preceeding

args. Arg applies to things not activity having and end

g. Problems

1. Hume in Inq.Hum.Und said no need for explanations

-Aq is appealling to an a priori notion of causation

h. Solution

1. Tend to be in favour of order cf Aqs single things, which

mod sci does not seem very sure about. Plus now tend to

arg that Univ is good for men (cf Aq where that waits

until later) .

2. Newtonian Physicsa is just as teleological as Arist.

3. Modern Science - not opposed to rel questions that have

been attacked since the enlightenment

a. Universe does seem to have begun

þ. cf ekpyrosis - circular

b. Connectedness of things - in reality of

probability in QM

c. Creation ab nihil - no energy needed

d. Anthropic principle

þ. Extreme chances vs Life

þ. Lagrangian

þ. Weak Force strength

þ. speed of light and electricity

þ. origin in unpredicatable breakdown

of original symmetries

þ. even out time of being on earth - partic

density of matter ??

þ. Not proven

þ. see Adair

4. In some respects Arg from design is untouched by

any developments in mod physics

5. Kant - even modern physics goes beyond realm of sense -

perhaps his arg was just enlightenment esprit ??

II. TIE IN KANTS ALLOWANCE OF AN ARCHITECT FROM

TELEOLOGY WITH KENNYS VIEW ON A UNIVERSE THAT BEGINS NEEDING

A CREATOR (SEE WAY 3) AND YOU HAVE A PRETTY GOOD PROOF.

IX. Other ways of Vat I being saved

A. Concurrence of many args - no proof conc,

but all point the same way

a. open to criticsim

1. no number of inc. proofs add up to a conc proof

2. cf Newman and a million diffs not = 1 doubt

3. but still seems poss for rational man

B. Ontology - rej, Aq + mod Caths, but provides aM poss.

C. Kantian Moral arg

D. Faith/Rel experience

a. Aquinas wld agree, but not totally

He was all about the power of Human reason, something

upheld at Vat I and part of Christian freedom,

whatever actions some in church take opposed to reason

Boswell and the Latin West; and the debate over the blessing of friendship today

Alan Bray

Summary

This note consists of some reflections on John Boswell’s Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe, with an eye to the relevance they might have today: to the current debate over the blessing of homosexual friendship. It is for this reason that these reflections focus on what John Boswell had to say on the Catholic west - where the debate now has its sharpest edge. These reflections are also a response to the perceptive arguments put forward by Elizabeth A R Brown and Claudia Rapp in ‘Ritual Brotherhood in Ancient and Medieval Europe: A Symposium’ Traditio Volume 52 (1997) pp. 261-381. What I have attempted here is to revisit the documents these historians employed and to apply a reading in different terms.

The argument I make below for the form of the rite that appears in latin europe to have corresponded to the adelphopoiesis edited by John Boswell was put forward in a BBC Radio programme a few days ago: ‘The Kiss of the Crusaders’ BBC Radio 4, 12 June 2.30pm produced by Tessa Watt and Helen Weinstein and introduced by Eamon Duffy. It anticipated some of the conclusions of my book on friendship in traditional society in england. The historians John Bossy and Maurice Keen joined in the discussion. The programme was designed as a popular presentation - there was an audience of approaching half a million listeners - and centred on a tomb monument to two english knights who died in Constantinople in 1391 and were buried there together. This monument is one of a number from medieval england that appear to show the traces of this rite.

Giraldus’s Topographica Hibernica

The implications of the material discussed in John Boswell’s book have I think been dismissed too easily and in particular the account he quotes from Giraldus de Barri’s Topographica Hibernica. This is not a sober and objective work but a piece of propaganda, intended to justify to its audience in catholic europe the invasion of Ireland by the Anglo-Norman army under Henry II in 1171. As evidence for Irish society a work of propaganda such as this is hardly reliable. Its value as historical evidence is rather I would suggest its indirect ability to preserve evidence of the values and prejudices of the audience that Giraldus was seeking to manipulate. In the course of this work, Giraldus describes a ritual confirming friendship which its audience could be expected in this way to recognise and value. Or rather to recognise as here debased by the blood that according to Giraldus among the Irish follows its treacherously pious beginning: